The next time you wander through a warehouse or storage yard, spare a thought for the humble pallet. Traditionally made of wood, with the majority designed to last only a single trip, these unsung items bear the weight of the ever-increasing goods transported around the world to meet the needs of a growing and increasingly prosperous population. In addition to their lack of longevity, they’re also not known for being ‘smart’, partly because of the high cost of adding tracking technology to them, compared to their value – you can often see them being offered on the roadside for just £5 – and their short lifespan.

However, this is starting to change thanks to improvements in material sciences, environmental concerns and the rise of low powered wide area technologies that have dramatically reduced the costs of connecting huge amounts of devices and enabled battery lives of up to 10 years.

Two companies at the forefront of this trend are RM2 International SA and Ahrma Pooling. They own pools of long-lived pallets that they hire out to logistics companies and are looking beyond just wood. The components of RM2’s pallet (the BLOCKPal) are made from glass fibre and resin using a process called protrusion. These are then glued and screwed together. Ahrma uses sustainably sourced hardwood MDF with a polyurethane water-proof and anti-bacterial coating from BASF, and according to Erik Ekkel, Ahrma’s IT director, the pallet is “fully repairable” because the components are glued together rather than being nailed together.

The two companies have taken a different approach to track and trace, with Ahrma opting for active RFID technology based on Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) technology (although it can also provide LoRa, Sigfox or LTE-M connectivity on request) and RM2 running trials using LTE CAT 1 technology, the precursor to LTE-M, although David Simmons, RM2 International’s CTO, says it now has devices that work with the new chips and AT&T’s LTE-M network, which covers the US. He adds that RM2’s pallets can be used in the US, Canada, Mexico and Europe,although he notes that while some pallets are being tested in Europe, all the deployments have been in the US, Canada and Mexico, where RM2’s major customers are located. The new technology works at low bandwidths, 200kbps and, according to Simmons, has very much better in-building penetration than conventional LTE.

Simmons also notes that previous technologies were much less suited to this whole, with GPS and 2G/3G links being power-hungry, while the devices themselves were very expensive – “so by the time you got a good working track and trace technology, you were spending a lot of money just to track an asset which was worth a lot less than the device you were putting on it.”

In both cases, the track and trace technology enables the companies’ business models – as without an automated and accurate way of tracking pallets and being able to invoice customers on a per day or per trip basis, it would be extremely difficult to operate a pallet hire business at scale, especially given the potential for human error and the increased value of the pallets, which would make pallet loss an expensive issue for the owners.

“We don’t sell the pallets,” says Ahrma’s Ekkel. “We rent them out as a pool and with our system, we can see remotely on our cloud-based dashboard how many pallets are where, so we can automatically invoice the customer [possibly on a per-day basis] and the customer does not need its own administration with how many pallets are coming in and how many go out – that’s all done automatically.”

Simmons says that one of RM2’s customers uses its system to flag up when pallets depart from a warehouse and it uses that data combined with Google Maps, its traffic data and the route to calculate an estimated time of arrival.

Meanwhile, Ahrma’s pallets are set up to gather temperature and shock data as standard (with the ability to add humidity and CO2 sensors as optional extras), which is extremely useful when transporting perishable or delicate goods, such vegetables, fruit, medicine, wine, and white goods. In the case of the latter, Ekkel says that a major washing machine and dishwasher manufacturer has told Ahrma that around seven per cent of the products it ships from its factory arrive at the warehouse with some damage.

Ekkel says the pallets can store three week’s worth of data, so that when they arrive after being shipped somewhere and move back into range of a gateway, their data “can be flushed into the cloud”, allowing the user to be able to see the history of their journey. He adds that this system is extremely helpful for insuring shipments – “we’ve talked to insurance companies already and they really like this”. The greater visibility enables them to determine at what point in the chain any damage occurred. However, much of the impetus towards adopting Ahrma’s system comes from large logistics companies’ innovation teams as with all the data it collects, “a customer can really optimise their logistics movements… The interesting discussions are always around the data collection and the pallet is almost a secondary discussion,” Ekkel adds.

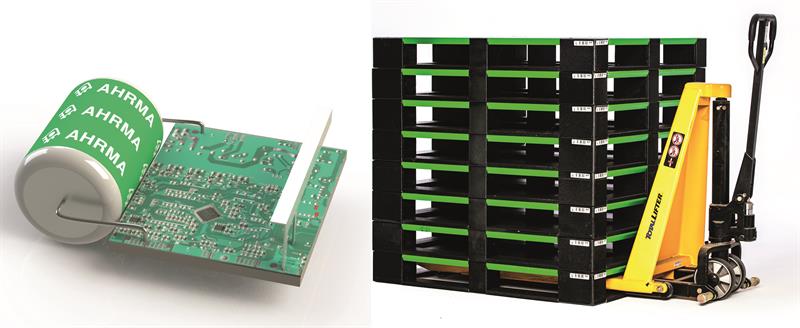

Left: the transponder used in Ahrma Pooling’s smart pallets, a stack of which is shown on the right

Simmons also highlights fresh produce: “From field to shelf is the all important metric and they want to know if things are stuck at particular points, especially if it is cross-border.” He adds that RM2’s system works across Canada, the US and Mexico, “So if you have something grown in Mexico that is being sold somewhere in the USA and it’s got to go through a set of distribution centres, you can see it move from the field to the dock of the supermarket. You can see where it’s being stopped, and if it’s being stopped for too long you can ask why.”

Adopting these systems is relatively straightforward. In the case of Ahrma, it provides its customers with its own IoT gateways, which it then installs in their premises in strategic locations, such as where goods are received or dispatched. The gateways require a connection to the mains and connects to the customers’ own networks via either Wi-Fi or Power over Ethernet, or an external 3G modem when those are not available.

The gateways can communicate with the pallets at a range of 60-100 metres, “so you would normally need a few gateways for a warehouse and this is a good thing”, says Ekkel, “because if you have three or more gateways in your warehouse with our software and triangulation algorithms, we can show [you] on the dashboard where pallets are located in the warehouse. So, with our infrastructure, the customer automatically gets a warehouse management system with positioning, which is normally a separate solution that costs a lot of money.” He also expects that, in future, gateway providers like Cisco will include Bluetooth connectivity as standard, at which point Ahrma will not need to supply its own gateways anymore.

One question Ekkel frequently gets is whether the Bluetooth transmissions (which are in 2.4 GHz) will interfere with Wi-Fi networks. He explains that the Bluetooth standard has done a really good job in ensuring co-existence with Wi-Fi, “so a Bluetooth network doesn’t disturb a Wi-Fi network”.

Simmons says that as far as everyone on the warehouse floor is concerned, RM2’s pallets are handled normally as they are sealed for life with no need to recharge, with the only difference being that “the pallets talk back to a central cloud-based server, and all the customers connect to that server and they can only see their own fleet of pallets”. He adds that customers can access a map-based system to see where all their pallets are on the map, but if they have hired “the best part of a million pallets, they’ll “probably just get dots everywhere”. Because of this, most of RM2’s customers prefer to use its ELIoT (Electronic Link to the Internet of Things) system’s API (application programming interface) to tie into their own systems to allow them to process the data as they wish.

Simmons points out that track and trace pallet systems are an aid to reverse logistics specialists who determine the most efficient way of getting things back to a central point after they have been distributed somewhere, as it removes the difficulties in locating material caused by relying on traditional human error-prone systems.

Ekkel sees environmental concerns as another driver for the adoption of long-lived smart pallets: “Most companies want to become more green and one-way throw-away pallets are of course not a good proof of good sustainable business.” He adds that Ahrma’s pallets are made from FSC certified wood and at the end of their lifetime are grown down to make new pallets.

The gains from greater efficiency and better use of materials enabled by connected pallets could make a major difference. AT&T recently completed a case study on the use of RM2’s connected pallets and it concluded that if they replaced just five per cent of the estimated 10 billion pallets moving around the world today, it would cut petrol consumption by 818 million gallons a year and save 7.3 million tonnes of CO2 annually.

There is also the issue of cross-border contamination – Simmons says that weevils and other insects can hitch lifts on wooden pallets and sterilising these is a much more expensive and difficult process than with pallets made from non-absorbent material.

RM2’s current focus on the technology side is working to improve the power usage on the pallet-mounted transponders, so that they can do more with them. “We are getting a lot of questions about being able to talk to other devices, such as a humidity monitor that is separate to the pallet [for example] – that’s one thing that’s on the roadmap probably next year,” Simmons says.

He also notes that while some large multinational companies and supermarkets operate “closed-loop pallet systems”, in which they are continually shipped back to distribution centres, sent for washing, returned and then sent out again, the “ultimate goal is to have an Uber for pallets”, which would be more of an open-loop system. “We believe that with this system we can do that, but there’s still a long way to go,” he concludes.

While mass adoption may be a few year’s down the road, the rise of smart pallets is a clear example of the new business models and ways of working that are being unlocked by the growing maturity of IoT technology and of the significant benefits it can deliver in terms of greater efficiency and a more sustainable way of doing business.